Blog Posts

Mapping out the game design space through prototypes

Game Design Documentation: Prototype Reflections

2025 Jan, 22ndDesigning a game is like grasping for a light switch in the darkness. Each prototype is your attempt to find that switch by reaching out in some direction into the unknown.

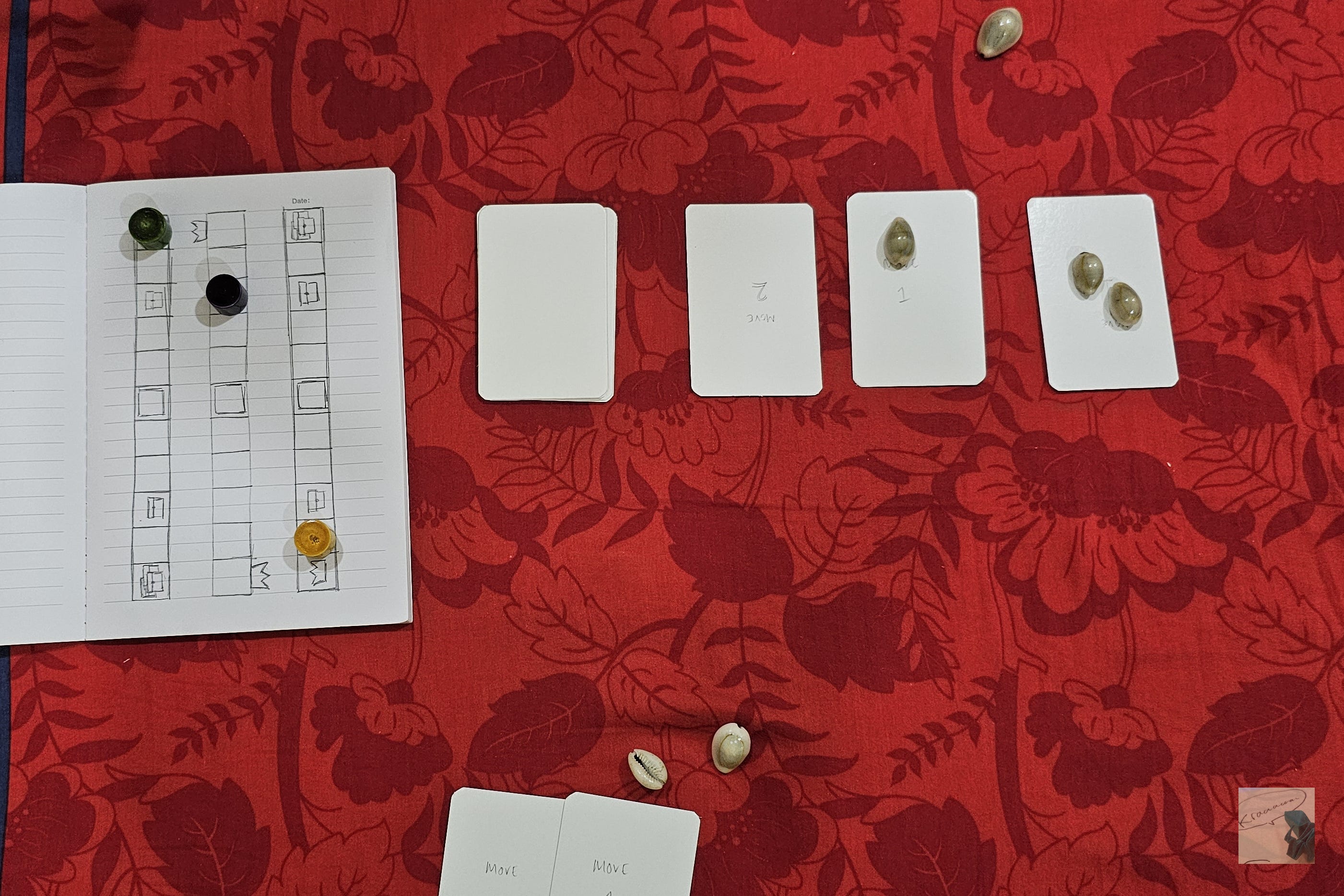

Photo by Shruti Parthasarathy

It helps if you record each venture into the darkness so that over time you build your own map of the game design space. You can refer back to that map later in the project to see where you have and haven’t explored. Or you may refer back to that map in a future project and see some connections that would presently help you. Each mapmaker has their own style of cartography - let me share my time-tested experience with you of how I record all of my game design prototypes. As always, take what works for you – and I’d love to hear what doesn’t work for you and why.

Stylized map of Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto, Japan

I call these documents Prototype Reflections and I use the following template for all of them:

Prototype Reflection: [PROTOTYPE NAME]

- Deliverables

- Reflection

- What is the goal of this prototype?

- What lessons did I learn from this prototype?

- Gallery

(What’s in a) Prototype Name?

I like to keep the prototype name short and simple even if it is mechanically descriptive: ‘Social Deduction Mafia Game’ or ‘Caltrop Core TRPG’ or ‘Unity Shaders’1 are all good enough. It’s the first bucket for my brain to associate with the prototype when I think about it or if I refer to it in conversation with my teammates/friends later.

Deliverables

The deliverables section is where we add the actual work generated after working on the prototype. This could be links, files, or executables - whatever lets us directly experience the work we created. Sometimes this is a PC build of a Unity Project, sometimes it’s a PDF of a print and play game, or sometimes it’s a Google Docs link to the first draft of a tabletop RPG system.

Reflection

The reflection section is the key to this document - it is where we learn the most from writing about our prototypes.

What’s the Goal?

Before I begin my prototype, I answer the question ‘What is the goal of this prototype?’ Blue sky thinking is great for ideation2 but I find that a good prototype seeks to answer a specific design question. The more detail in the question, the more you learn. Instead of waving our hands in the darkness, we pick a direction and reach out as far as we can go.I consider all of these as examples of good prototype questions:

Can we integrate RPG leveling mechanics and bullet-hell gameplay in a fun loop? Can we implement a compelling walking simulator with a focus on audio design and kitbash the 3D models from this one asset pack? Can our team create and implement an array of shaders to use in future projects? Can we make a game that uses twin-stick arcade controls?

The reason that we write this goal before working on our prototype is to keep ourselves accountable to our past selves. Meandering is part of the creative process, but recording the goal at the start allows us to check if we reached or see how far away we ended up. Both outcomes are valuable. After writing the goal, I only return to the document after I’m done prototyping - this is so I don’t update my goal in real-time to suit whatever result I’m observing as I work.

It’s like driving up to Los Angeles from San Diego without a map in hand. Maybe we leave San Diego and head in a generally North direction, hoping to see LA in two-ish hours3. Perhaps along the way we see the lovely beaches in Oceanside and stop for a detour. Actually, you enjoy Oceanside way more than you expected: it has great cafes, interesting shops and lovely weather; so you decide to stay there. Great trip! Let’s save Los Angeles for next time. Sometimes prototypes take us unexpected places, and we may as well enjoy the journey.

What did we Learn?

After I’ve finished my prototype, I answer the question ‘What lessons did I learn from this prototype?’ I allow myself a rambling, flow-of-consciousness style here because I want to get all my thoughts out here. We can always sift through the sand for gold dust later. Framing the question as ‘lessons learnt’ keeps our focus on our growth from the work, and not on failing to meet our original prototyping goal. It’s helpful to also think about whether you enjoyed working on the prototype. Would it be a project you’d be happy to work on for months on end if you decided to expand on it?We might also explore any new insights or unexpected surprises we experienced while working on the prototype. Perhaps we enjoyed rotoscoping animations and we’d like to explore them more in the future. Or perhaps we struggled with a technical implementation and now we realize we need to brush up on our vector math and matrices. Maybe we loved playing with the colors in the UI and we want to go study color theory. Or maybe we hated dealing with colors - and we never want to touch color theory with a ten foot pole. Let your emotions guide you, as usually your body viscerally knows before your brain comprehends.

Sometimes, I add a bullet list after my rambles to succinctly summarize my thoughts for my future selves (or my teammates).

Gallery

Finally, the gallery is where I add all photos, screenshots, GIFs, and videos of the prototype. I’ve learned the hard way that you can never have too many photos of your projects and prototypes. Take some photos. A picture truly is worth a thousand words; and a single video is probably an entire novella.

Into the Archives with Ye

We save our team prototype reflection files in its own database. This makes it easy to search back through and reference specific pieces of assets or code as we work on other projects.Hopefully, I’ve convinced you of the value of reflecting on and recording your thoughts on your work, even if it is a humble prototype. Memory is fickle; to me it’s considerate to my future self to share my state of mind when I’m most immersed in the work.

Here are links to my Prototype Reflection document template for your perusal, in PDF format as well as a Notion page you can duplicate.

1. If I made more than one ‘Unity Shaders’ prototype, the easy way to distinguish them would be to add the date of creation, or specify which shader visual effects I created. Either way, the name gives me a little more detail that helps with recall the prototype when I come back round to review it.

2. Lemarchand, Richard. “Blue Sky Thinking”. A Playful Production Process: For Game Designers (and Everyone). The MIT Press, 2021, p. 11-16.

3. In rush hour traffic? Pigs would fly.